Prejudiced and Prefabricated Judgements obscure the lives that were, are and can be lived in housing estates built during the communist period. Debunking these myths – these panel stories[1] – can help promote wider and deeper reflections on the communist period, postcommunist transition and the material politics of both the past and the present.

By Benjamin Tallis

Despite their best efforts neither jetset shock therapists nor home-grown dissidents and their various governmental inheritors have been able to make postcommunist transition a clean break with the past. Apparatchiks and functionaries were denounced and (occasionally) lustrated, only to re-appear as nomenklatura capitalists and even government ministers. Statues were removed, but the metronomic passing of time in their after-image triggers memory, not forgetting. Streets and metro stations were renamed, but we still know who Evropská and Dejvická used to be.

The persistent presence of the communist past is a key site of struggle for Czech (and Slovak) collective memory. Competing interpretations, both domestic and international, significantly impact the ways in which people can live today, how post-communist societies are structured and whom they are for. Material reminders of that time have come in for particular criticism and none more so than the paneláky, the concrete-panel blocks that make up the sídliště and sídlisky which became such prominent features of Czechoslovak socialist cities. While a nascent revisionism has begun, belatedly and hesitantly, to recognise the architectural quality and even (shock, horror!) beauty of Czech brutalist architecture, it tends to focus on particular marquee buildings (such as the Nova Scena of the National Theatre or the Nova Budova of the National Museum). Meanwhile the communist-era housing estates are still routinely damned from all sides.

However, recent research has shown that both domestic and international criticisms of the paneláky and sídliště are wide of the mark. Blinkered by ideology and blind to the plurality of panelák and project life lived both then and now, these flawed critiques are indicative of wider problems of both understanding and policy in postcommunism.

This essay sets out to debunk three of the most significant myths or ‘panel stories’ associated with communist era housing projects: (1) that paneláks and sídlištěs were a ‘communist’ idea that were imposed on Czechs and Slovaks from elsewhere; (2) that problems with high-density public housing are indicative of the futile and flawed pursuit of modernist and social-democratic goals; and (3) that people lived, live and will live badly in paneláks and sídlištěs.

Tall Tales & Sweeping Judgements

Condemned by some at the time of their construction as “cement deserts” good only as “battle grounds for high-rise brats,[2]” the estates provide an all-too-easy synecdoche for the time of their building; “monotonous and repetitive, banal, inhuman […] poor in quality[3]” or most commonly (and lazily) “grey”[4] or at least “grayish.”[5] Normally nuanced and even-handed judges have been moved to unequivocal castigation of the aesthetics and morals of the ‘structural panel buildings’ that make up the vast majority of Czech housing constructed between 1955 and 1990. Sean Hanley of the UCL School for Slavonic and Eastern European Studies describes the “monster estates” as “hideous” and “awful,” and Václav Havel famously spoke of “undignified rabbit pens, slated for liquidation.”[6]

The controversy and criticism that continue to batter these concrete facades, from both home and abroad, reflects and reinforces a particular politics of memory, identity and belonging. It stems from a combination of blanket judgements on the communist period, teleological notions of neoliberal postcommunist ‘transition’ and particular (Western European and North American) experiences and ideological interpretations of high-density social housing.

Negative Czech judgements on paneláks in popular discourse and the statements of well-known figures seem to stem largely from the circumstances of their making – they were built by the communists and must therefore not only be bad, but are a malaise forced upon Czechs (and others) by unwelcome intruders and occupiers.[7] The popular and academic focus on the myriad crimes and appalling injustices of the communist regime have helped to support such views.

These are undoubtedly important stories that needed to be told about life in communism. However, they are not the only stories of that time and cannot be used to sustain uniformly negative views of an era in which, under trying circumstances, people continued to live, laugh, love, have children and make the homes in which they could grow up. The regime failed in its totalizing ambitions, but has been posthumously been granted success that it could have only dreamed of in a totalizing memory of the time that erases the positives of this painful past.

Similarly, while institutional design and the processes of re-adopting democratic politics, market economics and re-integrating to international institutional structures have been highly significant, they have often obscured lived experiences of transition, what came before and what may come after.[8] This blinkering, combined with the prefabricated opinions of many Americans and Western Europeans towards large scale public housing projects has allowed skewed views of the material and social conditions of sídliště life to dominate past and present.

After the fall of the wall, it was easy for incoming investors, advisors and other ‘tutors’, keen to school the ‘children of the revolution’ in their neoliberal ways, to tar the paneláky with the same brush as their own concrete jungles. They knew of the riots in Toxteth and Brixton and heard in the Sídlištěs the echoes of the doomed Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis. The self-styled ‘tutors’ found eager prefects in the dissidents of the communist period, all too happy to run-down the remnants of a hated regime, often with little thought for the people who lived there. Unlike many dissidents and their quieter sympathisers, the Sídliště dwellers were not waiting for prime real estate to be restituted to them.

Many of these tutors also had a double interest in denigrating the communist past. It would both bolster their own superiority (and thus legitimacy as teachers) and enhance the case for neoliberal transition as a greater contrast to what had gone before, rather than a more social-democratic approach. Tearing down the old structures of ownership and usage was more feasible than destroying the paneláks themselves and raised the potential for Western-owned banks to introduce market rates to these rent-controlled worlds.

Social research conducted over the last two decades has questioned the basis for each of the criticisms leveled at Paneláks and sídlištěs, exposing them as mere ‘Panel Stories’. Challenging these stories and telling new tales of panelák life not only has specific relevance to these persecuted places but opens up the possibility of questioning the socio-political settlements of transition more widely. It can allow us to ask again what type of societies we want to build, who they are for and how they are constructed, as well to re-examine the various roles of the state, the market, the individual and the collective.

Detail from building at Sídliště Invalidovna, Prague

Detail from building at Sídliště Invalidovna, Prague

Panel Story 1: A Communist Idea, Imposed from Outside

Over the last five years, the writings of Kimberly Elman Zarecor have made a good deal of multidisciplinary Czech scholarship on paneláks and sídliště’s available to Anglophone audiences. Zarecor has exposed the double fallacy of claims that concrete tower blocks were a communist idea and that they were only accepted in Czechoslovakia under Soviet duress[9].

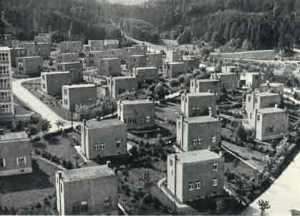

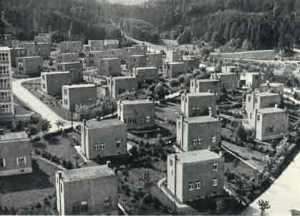

Zarecor highlights how far from being imposed from outside, the specific circumstances of postwar Czechoslovakia spurred the continuation and development of interwar architectural practices and politics to accelerate and intensify, but not intitiate, the development of prefabricated structural panel housing in the communist era. The construction technology for Czech paneláks owed its development to the Building Department of the Baťa shoe company in Zlín, which had been experimenting before the war with prefabricated building technologies. The architects Hynek Adamec and Bohumil Kula had continued these experiments during the war and headed the projects on new structural panel housing at the time when the department was incorporated into the communist Stavoprojekt building co-ordination system. Despite Zlín having been renamed Gottwaldov after Czechoslovakia’s first communist leader, Zarecor points out that Adamec and Kula were still working in the same office when developing the first panelák – the G-building (named for Gottwaldov).

Zlin, Bata building from Zlin.cz; Zlin workers housing, pre-war brick (erasmusu.com) and post-war concrete (zippomaniac.fr)

Far from following developments elsewhere, Czechs (and Slovaks) were actually ahead of the game in panel building. The crucial breakthrough – as Zarecor shows – came when an innovative solution was found to the problem of joining the concrete panels together in a stable way. The use of a series of steel ‘hooks’ and staples’ allowed for full exploitation of their structural properties and eliminated the need for an additional skeleton.[10] The pioneering architects who found this way previously worked for the feted (and avowedly capitalist) Baťa company and were actually continuing construction-technology research that had begun long before the communist takeover. It is also significant to note, however, that the ideas which inspired the social aspects of both the panelák and the sídliště can also be found in the first Czechoslovak Republic (as well as elsewhere).

The First Republic under the ‘Liberator-President’ and ‘philosopher king’ Tomas Garrigue Masaryk is widely hailed as the Czech golden age, a brief and glorious interlude of independence, after empire and before both Nazi occupation and Soviet subjugation. The wave of creativity in both culture and commerce that was unleashed during this time merits this golden reputation, with companies such as Baťa and Tatra stylishly propelling Czechoslovakia into the ranks of the top-six exporting economies in the world. The poetry of Vítězslav Nezval and Jaroslav Seifert; the painting of Frantisek Kupka, Jindřich Štyrský and – the already post-gender – Toyen; the buildings of local talents such as Josef Havlíček and Karel Honzík, Josef Fuchs and Oldřich Tyl, alongside those of proto-starchitects Adolf Loos and Mies van der Rohe, ensured that there was plentiful art to accompany the industry.

Karel Teige, Building and Poem (1927) & the Minimum Dwelling (1932).

However, like much of Europe at the time, the First Republic was also awash with radical Marxist ideas. A mixture of proactive idealism and reaction to the polarized living conditions of the time inspired those such as Nezval and Karel Teige – writer, architecture critic and ringleader of the radical Devetsil group – to rail against the inequalities and injustices they saw around them. They sought collective salvation through both art and industry, but saw that both should serve functional, social goals rather than being beholden to the monied mores of the market. Teige in particular struggled with the tension[11] between instrumental social function and liberating creative expression, but in architectural terms prioritized the former, arguing that beauty would spring from the minimal forms that would most efficiently serve their purpose.[12] Demanding that those at the sharp end of the housing crisis at the time receive only “the best of the best,” Teige publically upbraided Le Corbusier for abandoning such functional purity and effectively re-introducing decoration; he slammed Mies’ much-praised Tugendhat Villa as the “pinnacle of modern snobbery.”[13]

Villa Tugendhat, Brno, from the guardian.com

It is therefore no wonder that Zarecor is able to draw a clear line between the construction of paneláks and sídlištěs in the communist period and social tendencies in First Republic Modernism, which were, however, also strongly connected to non-marxist Bauhaus figures such as Walter Groupius. Although Stavoprojekt, a state-run system of architecture and engineering offices, replaced private practice in the late 1940s and changed the profession profoundly, the vast housing estates in many Czech and Slovak cities are, in fact, the fulfillment of an interwar vision of modernity that emphasized the right to housing at a minimum standard over the artistic qualities of individual buildings (a debate that Teiger wrestled with and which continues to animate discussions over functionalism and modernism’s social purpose into the present).

Zarecor highlights intensified construction of Paneláks, as the Czech version of what she beautifully terms “Socialism with a Modernist face” in the wake of the success of the Czech pavilion at Expo ’58 – the Brussels Dream of ‘One Day in Czechoslovakia’. The socialist students of Karel Teige – notably Karel Janu, Jiři Stursa and Jiři Vozelinek – that rose to prominent positions in postwar Czechoslovak architecture helped shape the estates. However, so too did Havlíček, Honzík and other non-Marxists who continued to build for the new regime, sharing the common idea that building housing was a social good.[14]

While it is almost certainly true that the scale and scope of panelák-based sídlištěs was greater in Czechoslovakia due to the communist takeover, it cannot be claimed that these architectures and urbanisms were imposed on Czechs from outside, nor that they were a communist-era idea. However, emphasizing the links, rather than the rupture, between the First republic and the Communist period goes against the currently dominant and highly Manichean politics of Czech collective memory that divides positive and negative in fairly bald temporal terms – 1918-38: Good; 1938-1989: Bad. 1989 onward: Good again (we hope).

Panel Building at Hloubětín, Prague

Panel Story 2: High-Density Public Housing as Failed Socialist & Modernist Dreams

Dissident attacks on paneláks have resonated with wider narratives of neoliberal transition about the role of government in society and related attitudes toward public housing. The ‘End of History’ consensus that laissez-faire, (neo)liberal-market-democracy is the only way to govern chimed with hostility towards high-density public housing as architecturally flawed, naively irresponsible and ultimately dangerous social engineering. Scepticism of government born from bad experience of a particular regime has met ideological opposition to the state as such. The failure of social housing projects in the West has been conflated with the failure of state socialism in the second world with both used as evidence of dangerous burdens of utopian dreams.

Buildings from Sídliště Invalidovna and Sídliště Cerveny Vrch, Prague

Such attacks generally eschew the controversialist, yet architecturally adventurous and open-minded iconoclasm of Charles Jencks.[15] They tend to prefer the offended traditionalism of Simon Jenkins, whilst retaining their mutual weakness for décor and ornament – eyebrows simultaneously arched and furrowed in facial gymnastics that Alec Guinness would be proud of. Crucially they often combine this aesthetic position with the selfish Hayekian/Friedmanite socio-economic Darwinism that seeks to entrench power for those who already have money and which, since ’89, has come disguised as freedom. A supposedly hard-headed pragmatism in which politics is disguised as economics; a refusal to be suckered into social dreaming. Often accompanied (in some quarters at least) by faux-rueful laments for the failure of stillborn social schemes that never had a chance, they are wheeled out time and again as evidence for why even marginally idealistic or minimally visionary social endeavours can never work.

The Death of Modern Architecture

Long before Jencks famously used the dynamiting of this massive and ill-fated housing project to proclaim the death of Modern Architecture “on July 15, 1972 at 3:32pm or thereabouts” the Pruitt-Igoe story had come to symbolise the supposedly hopeless futility of well-intentioned social housing in the US. A recent documentary film, The Pruitt-Igoe Myth,[16] exposes even this – the nadir of all the panel stories – as just that, a myth. The documentary, which takes an academically informed, socio-anthropological approach, effectively refutes the charges against the architecture of Pruitt-Igoe (and by implication against the principles of modernist-inflected high-rise and high-density public housing in general).[17] The joy with which the initial residents recall first moving in to the sufficiently spacious and well-appointed apartments (particularly in comparison to the slums where many had previously lived) is manifest. One resident – Ruby Russell – who moved into an apartment on the 11th floor coined the affectionate and memorable term “the poor man’s penthouse” to describe her apartment, while others describe the feelings of community, of safety and the possibility this provided for children to play and adults to live.

However, this was not to last. As the documentary shows as it details the total collapse of this housing project to the point where the police were afraid to enter and the tower blocks ended up being dynamited, this fate was largely pre-ordained. Cutbacks to the original design and the failure of the 1949 US Federal Housing Act to provide any maintenance money for such projects – requiring that such funds came from the rents paid by the low-income tenants – was the first nail in its coffin. Racism in both planning policy and the everyday practices of citizens continued de facto segregation policies long after they became de jure impermissible.[18] The combination of ‘white flight’, a declining city population (robbing it of necessary tax revenues to pay for essential services, including housing maintenance), the selling off of the downtown to property developers and official encouragement for sprawling suburban, low-density housing at the expense of the rotting urban core meant that the estate failed within grim socio-economic context. Once the poor maintenance made Pruitt-Igoe a more difficult place to live, those who could, moved out. Low occupancy rates further diminished the money available for upkeep and repairs, unleashing a vicious cycle of decline and degradation. As the documentary powerfully shows, this was not accidental. Rather, it was rather the result of the deliberate diminution of governmental power to act in a socially progressive manner in a politico-economic environment stacked against the most disadvantaged and predicated on the myth of the socially-unencumbered, all-consuming individual.

Park Hill, Sheffield, bdonline.com; the guardian.com and Robin Hood Gardens from detail-online.com

Significantly, the documentary specifically links the failure to support social housing to its associations with socialism, which both during the cold war and in the aftermath of ’89 made it ‘un-American’ and thus taboo in the US. While European experiences of public and social housing have not been as extreme as Pruitt-Igoe, the problems of housing estates such as Park Hill in Sheffield and Robin Hood Gardens in London, as well as many of the French banlieues can similarly not be blamed on their modernist (or, too-often, modernish) architecture, nor on the social intentions that inspired their construction. Rather, it was the failure to adequately address the underlying social conditions that prompted their creation and then the lack of conviction in backing the estates – with proper materials and maintenance – to provide (part of) the solution that sealed their fate.

That this lack of conviction held after the fall of the Berlin wall is not surprising. The very construction of such estates as a response to the demand for rapid urbanization and the ongoing postwar housing crisis in communist countries can be described after ’89 as “arrogant”[19] or dismissed as being “in the best traditions of vulgar Marxism” which apparently implies that, “the Communist regime believed that people were shaped by their environment.”[20]

It would be hard to think of a government – or indeed practically any other institution – that didn’t believe people were to at least some degree shaped by their environment. Indeed the prospect of people being impervious to their built environments would mean the end of architecture as anything more than art, or worse, decoration. When Sean Hanley claims that this substantiates his charge that the building of the paneláks was ideologically motivated, the point made by Michel Foucault and echoed by Slavoj Žižek that ideology is at its most powerful when it is most hidden, should also be considered in relation to the ‘pragmatic’, post-’89 treatment of social housing and the damage done more widely to ideas of social democracy and transformative governance by the collapse of communism and the neo-liberal consensus that filled the vacuum.

Panel Building at Hloubětín

Panel Story 3: People Lived and Live Badly in Paneláks and Sídlištěs

The fall of Pruitt-Igoe, the Brixton and Toxteth riots and the postmodern malaise that long beset the Unité d’Habitation and its ilk have been particularly unkind to millions of Central & East Europeans. They have been forced to belatedly ‘learn’ that the places in which they grew up, laughed, loved, raised children, realized creative activities, plotted defiance, cohabitation, collaboration or escape and where they created their cosy dens[21], insulated to some degree from the party regime, were no longer appropriate for their lives as ‘New Europeans’.

Sídliště Invalidovna

Crucially however, as even noted by critics[22] of the appearance and intentions of the paneláks, the social mix of the communist-era housing projects was very different than that of their counterparts in the West. In the second world, largte numbers of people from different walks of life and from varied social strata finding themselves (willingly or otherwise) thrust into high-rise neighbourhoods. This is partly due to the sheer number of people who live in such developments. Zarecor[23] quotes figures of 3.1 million people living in 1,165,000 apartment units in 80,000 paneláks in Czech Republic. With almost a third of the total population and nearly half the city of Prague living in paneláks, the issues facing postsocialist sídlištěs are, in most cases, very different than those experienced by residents in their deprived and marginalized western counterparts.

Building at Sídliště Dablice

Many communist-era estates are well-planned. Well-connected and well-provided for communities: house-proud and successful places. Their abundant and well-kempt common spaces (leafy in summertime, albeit rendered climactically bare in winter) host a variety of public services and private activities and allow collective grandmothering in the ample and adventurous social space they provide for children. There was not the same stigma attached to living in these places and as the artist Eva Koťátková argues, these were places where many people grew up happily and well, learning to be the creative and independent, experiencing concrete as schoolyard rather than jungle and certainly not succumbing to the attempts to create new uniform ‘Socialist [Wo]Man’:

I was born in Prague, grew up in one of the typical grey block-houses on the periphery and went to school there. Many people find this kind of architecture awful or boring but I have a strong nostalgia connected with this place – a place of the most formative periods of my life. Many motifs appearing in my work have their origin in the time of my childhood and adolescence and in the specific atmosphere of this location.[24]

Koťátková’s comments are not the isolated opinion of a nostalgic or contrarian artist. Zarecor’s work also draws upon several academic studies that show consistently high levels of satisfaction with sídliště life. Research conducted in 2001 by Lux and Sunega showed that 64% of Czechs considered their accommodation ideal and only 11% planned to move within three years. Moreover, Zarecor also cites studies that show that this is not a new trend, with many sídliště residents recalling moving to their new Haviřov homes in the same excited and reverent terms that the Pruitt Igoe tenants did. Recent work by Eva Špačková and Martin Jemelka in the Hranice sídliště in Karvina also shows generally high degrees of satisfaction, although mixed with calls for further improvements relating to upkeep and noise issues. As Špačková put its in an interview with Zarecor:

Generally it is possible to say that the majority of imperfections in the housing development, according to the opinions of the residents, are not conditional on architectural solutions but rather on the unmaintained, disordered, and unsatisfactory control and commercial abuse of public space and the former civic facilities. [25]

Hotel Kupa at Jižní Město

In a widely cited ethnographic study of the Prague sídlištěs at Jizni mesto and Jihozapadni Mesto, French anthropologist Laurent Bazac-Billaud concluded that people in paneláks generally know their neighbours and that both social and transport networks not only exist but also work.[26] Furthermore, Hanley repeats Bazac-Billaud’s finding that:

panelák life is based on a intense drive for privacy and individuality. Inside their standard panelák flats – identical in layout and to thousands of others the length and breadth of former Czechoslovakia – the key impulse of Czech panelák residents is to create their own private worlds.

This is still however not enough for Hanley who claims that “In a democratic society, [paneláks] would never have been built. Such hideous-looking, poorly planned public housing would quickly have attracted criticism and protest (as it did in the West). In a market economy, no one with any money would have invested a crown into a panelák flat.”

London’s Broadwater Farm Estate, from trainwalkslondon.com and flickr.com

Hanley’s critique could be read as a dire warning about the potential fate of paneláks in the postcommunist period after the end of rent controls, although currently this has only happened in exceptional cases. In the town of Most, the semi-ghetto of Chanov carries the real echoes of Pruitt-Igoe, not in its architecture, but in the social neglect that led to the decay and near abandonment of this Roma-majority housing estate. Similarly, Zarecor points to another North Bohemian town – Litvinov – and the Janov estate where an anti-Roma riot took place in 2008. Research conducted by a team lead by the prominent geographer Luděk Sýkora showed that the situation in Janov had been exacerbated by the sale of municipal apartments to ‘investors’ who refused to invest in repairing or upgrading the buildings and rented the declining apartments to low-income Roma groups, helping to create social segregation and stoke racial tensions.[27]

Chanov, Most, from wikimapia.com; Pruitt-Igoe from Radiantwriting.hubpages.com

In many more cases however, the right-to-buy schemes allowed tenants to purchase their apartments affordably from municipalities and rent controls remained in place until recently. Right-to-buy schemes were balanced with incentives to form tenants associations and residents committees in order to be able to benefit from EU-funded refurbishment schemes. These schemes have largely consisted of the installation of new windows, doors, elevators and the application of fixed Styrofoam cladding directly to the outside of paneláks, which are then covered with plaster in order to improve insulation. Residents have then been able to choose from a variety of colours to repaint the new cladding, eliminating the darkness at the edge of town. However, transforming the dreaded grey into what Zarecor terms a ‘rainbow’ of colours threatens to create what Špačková terms “multi-coloured kitsch.” Zarecor too warns against the loss of architectonic detail such as the definable edges of panels or surface texture which give the buildings a sense of proportion and without which they risk becoming “cartoon likenesses in the shape of apartment buildings with undifferentiated surfaces.”

Popular with residents, these largely cosmetic renovations seem to please Hanley, who in a later piece states “After this beauty treatment the hideous grey paneláky look pretty civilized” passing in an augenblick, for Holland or Germany. This confirms Hanley’s mainstream hierarchical view of transition (where success equals imitation of the West), but also Zarecor’s observation that, if all that took was a lick of paint, then perhaps there wasn’t so much wrong with them in the first place.

Sídliště Rajska Zahrada (Paradise Garden)

Building New Panel Stories: Re-evaluating and reviving the realities beyond the myths

The difficulty of disentangling aesthetic judgements on ‘grey’ or ‘ugly’ panel buildings from their context in the politics of communist memory and the particular political economy of the post-89 world makes it unsurprising that they should provide rich material for visual artists with social sensibilities. That artists with praxis as different as Veronika Drahotová, Tomáš Džadoň, Patricie Fexová, Eva Koťátková and Katerina Šedá should find inspiration or fascination in these massive structures and micro-societies speaks to their significance as sites for the interaction of and negotiation between public and private, uniformity and individuality, enabling constraints and bounded freedoms.

The work of scholars such as Kimberly Zarecor, Eva Špačková, Laurent Bazac-Billaud and Luděk Sýkora, as well as the engagements of the aforementioned artists call into question what we know about paneláks and sídlištěs and the contexts in which we know it. This challenges the how we remember both the public politics and the private lives of communism and the ways they have been re-negotiated in transition. It questions the social relations that are possible on housing estates today and between the estates and elsewhere. In turn this prompts us to consider who we live with, how we want to do so and to what extent we can achieve that. It questions the underlying assumptions of post-communist societies and they ways these societies are constructed – now and in the future – as well as who they are for.

Paneláks and sídlištěs are too often seen merely as monumental milestones on the way to a future that was never built: as inconvenient reminders of a past that would be better forgotten or as hangovers of uneasy dreams. Zarecor rightly calls for the rehabilitation of paneláks, which would act as a catalyst for re-appraisals of other aspects of Czech society. If this is to happen, then the old myths of outside imposition, misdiagnosis of the ills of social programmes and social democracy need to be exposed. Fallacies of indignity and malicious attacks on panel dwellers need to be put to rest in order to better deal with real emergent inequity and emiseration. To start telling new panel stories, we need to experience and embrace the diversity and vibrancy of sídliště life, aesthetically and socially, from the clean neo-functionalist lines of the Invalidovna estate to Ďáblice’s open green spaces, Jižní Město’s thriving brewery and the panoramic views from the Hotel Kupa

This is a re-drafted version of a piece that was initially published hard copy in Vlak 4, Prague, London, New York, Melbourne, Paris, Amsterdam: Eqqus Press (2013) and is also featured in Abolishing Prague, ed. Louis Armand, Prague: Litteraria Pragensia (2014).

[1] The title refers to Věra Chytilová’s legendary film ‘Panel Story’ which provides a supposedly candid, but largely negative look at the early days of the Jižní Město housing estate.

[2] From the poem Jižní Město (South City) by Jiří Žáček, reproduced in From a Terrace in Prague, ed. Stephan Delbos (2011) Prague: Litteraria Pragensia

[3] As noted by Els de Vos’ (2012) review of Lynne Attwood’s Socialist Housing in the Eastern Bloc: Gender and Housing in Soviet Russia and Kimberly Elman Zarecor’s Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity, published in Technology and Culture, 53 (2), April 2012, pp. 465-469

[4] Sean Hanley (1999) ‘The Discrete Charm of the Czech Panelák, Central European Review http://www.ce-review.org/authorarchives/hanley_archive/hanley22old.html

[5] Ivan T. Berend as quoted in Zarecor (2012) Zarecor (2012) ‘Socialist Neighbourhoods after Socialism: The Past, Present and Future of Postwar Housing in the Czech Republic’, East European Politics and Societies, 26: 486

[6] http://www.praguepost.com/archivescontent/40712-still-standing.html

[7] De Vos (2012).

[8] e.g. Alison Stenning & Kathrin Hoerschelmann (2008) History, Geography and Difference in the Post-socialist World: Or, Do We Still Need Post-socialism? Antipode, 40(2): 312-335

[9] Zarecor (2009) ‘The Rainbow Edges: The Legacy of Communist Mass Housing and the Colorful Future of Czech Cities in Peggi Clouston, Ray Kinoshita Mann, Stephen Schreiber, eds. Without a Hitch – New Directions in Prefabricated Architecture. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/wood/2008/; Zarecor & Eva Špačková (2012) ‘Czech Paneláks are Disappearing, but the Housing Estates Remain’, Architecture & Town Planning (Architektur & Urbanizmus), 34: 288-301;

[10] For the fullest treatment of this, see Zarecor (2011) Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia 1945-1960, Pittsburgh University Press: Pittsburgh, PA.

[11] See for example Peter Zusi ‘s excellent (2004) ‘The Style of the Present: Karel Teige on Constructivism and Poetism’, Representations (88); & (2008) ‘Tendentious Modernism: Karel Teige’s path to Functionalism’, Slavic Review (67:4).

[12] e.g. Teige (2002[1932]) Nejmensi Byt (The Minimum Dwelling), MIT Press: Cambridge MA, trans Eric Dluhlosch

[13] Karel Teige, The Minimum Dwelling, p6.

[14] Zarecor (2011).

[15] Jencks (1991 [1977]) The Language of Postmodern Architecture, New York: Rizzoli

[16] The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011) dir. Chad Friedrichs.

[17] See for example Oscar Newman (1975) ‘Reactions to the Defensible Space Study & Some Further Findings’ International Journal of Mental Health vol 4(3):48-70.

[18] See also Elizabeth Birmingham (1999) ‘Refraining the Ruins: Pruitt-Igoe, structural racism, and African American rhetoric as a space for cultural critique, Western Journal of Communication, 63:3, 291-309

[19] Radio Prague’s Martin Mikule – http://www.radio.cz/en/section/letter/panelák-housing-estates-the-indelible-heritage-of-communism

[20] Sean Hanley (1999) ‘The Discrete Charm of the Czech Panelák, Central European Review, http://www.ce-review.org/authorarchives/hanley_archive/hanley22old.html

[21] See the Czech film Pelíšky (literally translated as ‘Cosy Dens’), directed by Jan Hřebejk.

[22] Sean Hanley specifically notes this in his 1999 piece.

[23] Zarecor (2012).

[24] Interview with Luigi Fassi in Koťátková ‘Documentation 2’

[25] Zarecor (2012).

[26] Hanley (1999) and Kristina Alda, writing for the Prague Daily Monitor both reference Bazac-Billaud’s work. http://praguemonitor.com/2009/10/27/praguescape-pink

[27] Sykora et al (2010), Rezidencni Segregace, Univerzita Karlova & Minesterstvo pro mnistni rozvoj v Ceske Republice.

The following is a rough outline of what I said (it doesn’t correspond exactly to the words used but is close and gets the meaning across) – for those who can’t pick up the English over the Czech interpreter. The questions from the interviewer are followed by my answers

The following is a rough outline of what I said (it doesn’t correspond exactly to the words used but is close and gets the meaning across) – for those who can’t pick up the English over the Czech interpreter. The questions from the interviewer are followed by my answers